The self is an enso circle drawn on the blankness of no-mind. The guru is simply a finger pointing at that calligraphic moon.

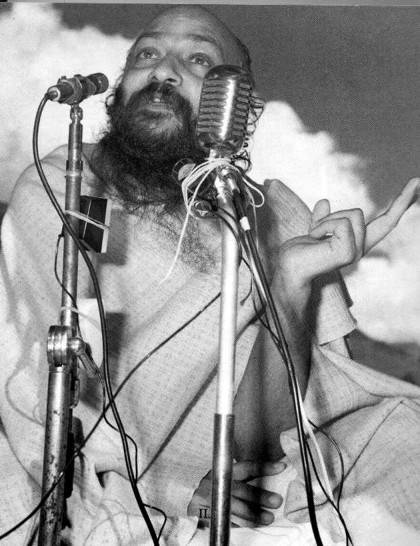

In 1964 during an early meditation camp at Mt. Abu, the man who would later be known simply as Osho outlined his vision. “I see man engulfed in deep darkness. He has become like a house whose lamp has been snuffed out on a dark night. Something in him has been extinguished. But a lamp that has been extinguished can be relit. I see as well that man has lost all direction. He has become like a boat that has lost its way on the high seas. He has forgotten where he wants to go and what he wants to be.”

He maintained that there was hope for humanity, however: “Although there is darkness there is no cause for despair. The deeper the darkness, the closer the dawn. In the offing I see a spiritual regeneration for the whole world. A new man is about to be born and we are in the throes of his birth.” This revolution would not come about, Osho stated, unless everyone worked toward it. Sitting back and waiting was not an option. “We cannot afford to be mere spectators. We must all prepare for this rebirth within ourselves. “The approach of that new day, of that dawning, will only happen if we fill ourselves with light. It is up to us to turn that possibility into a reality. We are all bricks of the edifice of tomorrow and we are the rays of light out of which the future sun will be born.” (The Perfect Way, 3 June 1964)

Despite objecting over the years to the traditional notions of Indian sannyas and ascetic renunciation, in 1970 Rajneesh gave sannyas for the first time. In the discourse that followed, he announced, “To me, sannyas does not mean renunciation; it means a journey to joy bliss. To me, sannyas is not any kind of negation; it is a positive attainment. But up to now, the world over, sannyas has been seen in a very negative sense, in the sense of giving up, of renouncing. I, for one, see sannyas as something positive and affirmative, something to be achieved, to be treasured.” (Krishna:The Man and His Philosophy, 28 September 1970) He gave his sannyasins new names and instructed that they wear the traditional sannyas colors and a rosewood mala with his picture attached. He infuriated traditional Hindu religious leaders by giving his followers the honorifics “swami” and “ma.”

His initiatory tradition differed dramatically from the sannyas of the past. He stressed that his disciples should embrace the world not reject it:

It is true that when someone carrying base stones as his treasure comes upon a set of precious stones, he immediately drops the baser ones from his hands. He drops the baser stones only to make room for the newfound precious stones. It is not renunciation. It is just as you throw away the sweepings from your house to keep it neat and clean. And you don’t call it renunciation, do you? You call it renunciation when you give up something you value, and you maintain an account of your renunciations. So far, sannyas has been seen in terms of such a reckoning of all that you give up — be it family or money or whatever. (Krishna)

He spoke openly about the spiritual nature of sex and spoke out against many of the leading religious leaders of his time. He later coined the phrase “Zorba the Buddha” to describe his vision of the new humanity. He emphasized that his new sannyasins should be both spiritual and worldly.

If sannyas, as I see it, is an acquisition, an achievement, then it cannot mean opposition to life, breaking away from life. In fact, sannyas is an attain. ment of the highest in life; it is life’s finest fulfillment. And if sannyas is a fulfillment, it cannot be sad and somber, it should be a thing of festivity and joy. Then sannyas cannot be a shrinking of life; rather, it should mean a life that is ever expanding and deepening, a life abundant. Up to now we have called him a sannyasin who withdraws from the world, from everything, who breaks away from life and encloses himself in a cocoon. I, however, call him a sannyasin who does not run away from the world, who is not shrunken and enclosed, who relates with everything, who is open and expansive. (Krishna)

Over the course of his life, Osho spoke literally millions of words in public and small discourses in both English and Hindi. These have been published as several hundred books and numerous translations. Throughout all these words, common threads run. The nexus of teachings was individuality and personal responsibility. Each person should become their own light, rather than relying on that of another, he taught. Discussing an old Hasidic story he said:

I meet you on the road; I have a lamp. Suddenly, you are no more in the dark. But the lamp is mine. Soon we will depart, because your way is your way and mine is mine. And each individual has an individual way to reach to his destiny. For a while you forget all about darkness. My light functions for me as well as for you. But soon the moment comes when we have to part. I follow my way; you go on your own. Now again you will have to grope in the darkness and the darkness will be darker than before.

So don’t depend on another’s light. It is even better you grope in darkness — but let the darkness be yours! Somebody else’s light is not good; even one’s own darkness is better. (The True Sage, 11 October 1975)

Over the course of 30 years, he systematically deconstructed all the forces that act to stifle the individual. During the 70’s he gave extensive lectures on just about every religious tradition. He later described this as speaking through others’ voices so that he could be heard by people who had grown up within the various world religions. In the early 80’s he entered a period of public silence. When he emerged from his silence in 1984, he began speaking out against all religions. His teaching, he said, was in favor of religious without the need to be part of a religion. In his first discourse, he spoke out against belief, saying that belief always carried doubt along with it and neither was necessary for one who had experienced spiritual truth.

He began mercilessly dismantling the world religions. The first to receive his attention was the one that had grown up in his name “Rajneeshism.” He publicly repudiated the religion and rejected the notion that he was a guru. Subsequent to this rejection of his own cult, he turned his razor-sharp analysis on the other major religions—including notable attacks on the papacy and the Reagan administration.

The only traditions he spared were the world mystery traditions, Sufism, Hasidism and Buddhism. The he described as the heart or truth of religion, where Islam, Judaism and practiced Buddhism was simply a reflection. Osho displayed a natural affinity to the teachings of the Buddha, and Zen Buddhism in particular. The 16th Galaway Karmapa, leader of “Black Hat” school of Tibetan Buddhism, recognized Osho as a living Buddha. Osho spent the last years of his life discoursing almost exclusively on the teachings of a wide and often obscure selection of Zen masters.

During these later years, he repeatedly noted that no one would follow him; that he would leave no successor. He instead maintained that he had prepared his people to be his successor. He would be dissolved into all of them when he left his body. “Stick me under the bed and forget about me,” he told his handlers.

Osho ended his last public talk given April 1988 with the word sammasati, the final word of the Buddha. Like Shakyamuni Buddha, he reminded all his sannyasins that they were each buddhas.

Osho was the epitome of a “crazy wisdom” master. He taught through provocation and the unexpected pushing of buttons as much as he did through discourse and meditation. When he taught in India, he spoke openly of sex and openly attacked the purity of the the mythic image of Mahatma Gandhi. After he came to America, a land not shocked by the frank discussion of the sexual, he played an amazing joke on American consumerism. The United States as a culture glorifies in the material acquisition of wealth. The conspicuous display of opulence is a de facto presentation of status. Ironically, America holds a completely opposite ideal for its spiritual teachers. Due in no small part to our protestant roots, our religious leaders have to be ascetic to be trusted. Rajneesh entered this mix and immediately attempted to out display the most glittering facets of American consumer culture. He wore diamond encrusted Rolexes and sunglasses and drove a fleet of lavishly painted Rolls Royces. He himself asked the question, why does one man need with a Rolls Royce for every day of the year and all the exact same make and model and with only one road to drive along? At the end of the Oregon commune, his fleet totaled almost 100 cars.

I first experienced the carnival fun park that is Osho’s teachings through the unlikely and unspiritual avenue of ABC’s Nightline. The year was 1984 and I was 14. The ABC National News with Peter Jennings ran a promo for that night’s Nightline. Seemed as if an Indian guru was causing some havoc in Oregon. In speaking of his numerous interviews with the world press, he said he spoke simply because someone might be listening